When was AI born? There’s a test for that.

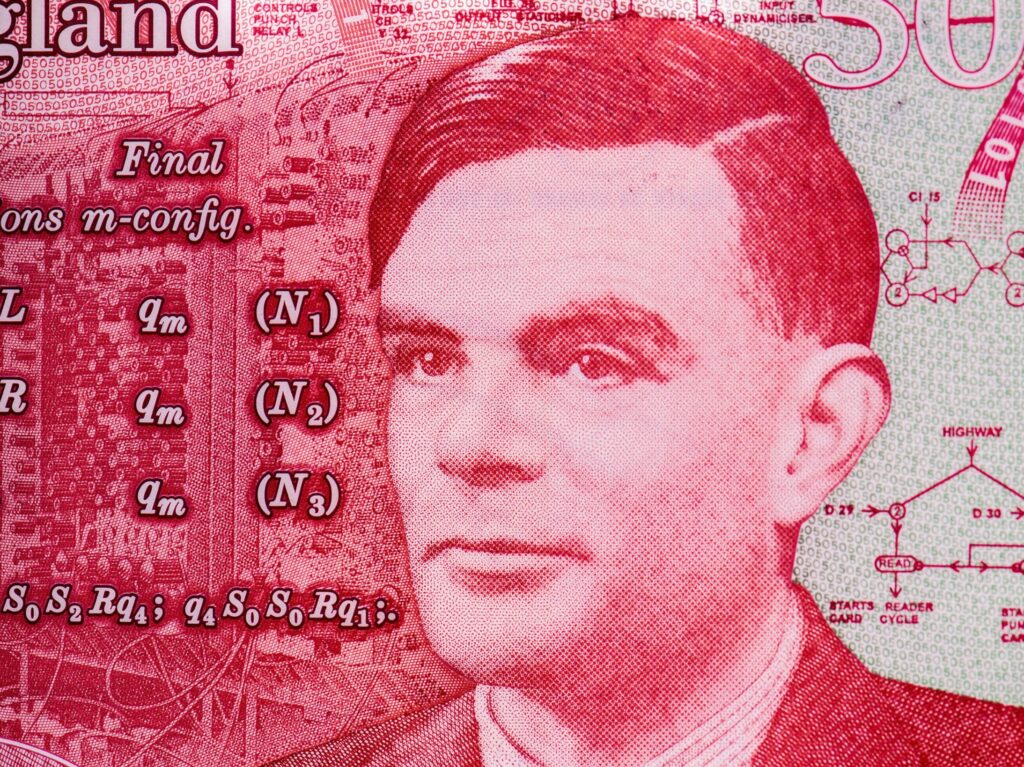

One of the pioneers of artificial intelligence was Alan Turing. He’s renowned for both his achievements during World War II, and the development of artificial intelligence (AI).

To this day, the Turing test is used to determine the ability of a machine to use natural language.

In this blog article you will find two paragraphs. One of them was translated by an algorithm and the other by a human translator. Can you guess which one was done by a robot?

But before we start the Turing test, let’s learn the story of this outstanding scientist who, like no other, has contributed to the development of artificial intelligence.

A brief history of Alan Turing and the Enigma

Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23, 1912 in London.

During his time at King’s College in Cambridge, he was impressed with Principia Mathematica by Bertrand Russel and Alfred North Whitehead.

He also studied the works of John von Neumann, which most likely inspired him to develop a model of a thinking machine.

Although Turing considered himself a pacifist, his views were quickly challenged by the turmoil of the war.

The scientist accepted the job offer at the Government Code and Cypher School in Bletchley Park. The team, codenamed “Ultra”, was tasked with developing “cryptologic bombs” aimed at ultimately breaking the Enigma code.

In 1942, Alan Turing constructed a calculating machine that managed to decipher German messages. Poles also contributed to the construction of the machine and breaking the code, which was officially admitted years later.

The Turing Test

The Turing test is very simple. Human judges are supposed to have a natural conversation with a mysterious interlocutor, who can be a human or a machine.

Five machines and one judge participated in the first study in the 1950s.

If the judge is not able to tell whether he is speaking with a real person or not, then it is considered that the machine passed the test. It is said that the computer must convince at least 30% of the judges.

In 2014, for the first time in history, a machine managed to pass the Turing test.

During the several-minute chat the computer convinced the judges that it was a human – 13-year-old Eugene Goostman.

Obviously, Eugene was nothing more than an intelligent algorithm which managed the conversation so well that the judges were tricked by his artificial identity.

The date when the computer “beat the man” was also symbolic – it happened exactly on the 60th anniversary of the tragic death of test creator Alan Turing, who committed suicide as a result of forced drug therapy which was supposed to “cure” him of homosexuality.

Although the results are not going to be objective or methodologically correct, we would like to invite you to do our test.

Here are two paragraphs taken from a popular science publication which were translated from Polish into English by a human and an algorithm.

Can you guess who the author of the translations is?

Extract no. 1 – Bot or not?

The fact that psychologists and doctors are reluctant to use mathematics and machines for diagnosis and therapy is nothing new. During my first research attempt on the topic, it took me only an hour or so to go back as far as to the 1920s, when the first articles with logical arguments for replacing the diagnosis made by a human (a clinician or a doctor) with statistical diagnosis (based on actuarial tables, statistical calculations and the like) were published.

Tomasz Witkowski, Zakazana Psychologia, Wydawnictwo Bez Maski, Wrocław 2019, s. 272.

Extract no. 2 – Bot or not?

Using LED devices at night interferes with the natural rhythm of sleep, the quality of sleep, as well as vigilance and the feeling of being well-rested during the day. In the penultimate chapter we will discuss the serious social and public consequences for the health of the population. As many of you I have seen small children use tablets during the day… …and in the evening. I don’t deny that they are wonderful devices. They enrich our lives and the education of young people. The problem is that the technology associated with them pours powerful doses of blue light into their eyes and brains, which has a devastating effect on sleep, which young, developing brains so desperately need.

Matthew Walker, Dlaczego śpimy. Odkrywanie potęgi snu i marzeń sennych, Wydawnictwo Marginesy, Warszawa 2019, s. 304.

Can you decide which excerpt was translated by the algorithm and which by the human?

Build better AI solutions for your customers with high-quality speech, image, and video data. Contact us today.